Mania Akbari

The Night

Mania Akbari, 2023

The Night I

80 x 120 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2023

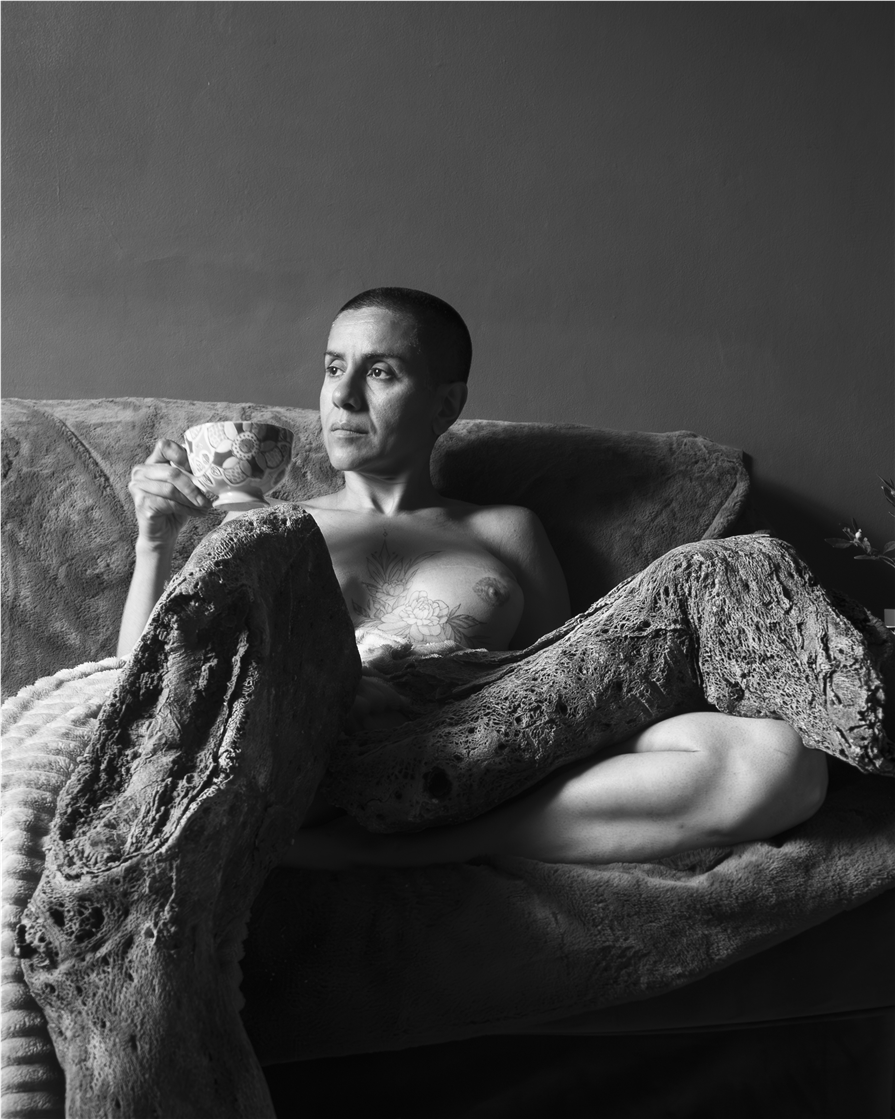

Allegory of Fortitude

80 x 60 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2023

Allegory of Fortitude II

80 x 60 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2023

The Night II

80 x 120 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2023

Indominus II

80 x 120 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2023

Allegory of Fortitude III

80 x 60 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2023

The Sleep Of Reason

80 x 53 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2023

Allegory of Fortitude IV

30 x 20 cm

framed size: 53 x 43 cm

Mania Akbari, 2023

Allegory of Fortitude V

30 x 20 cm

framed size: 53 x 43 cm

Mania Akbari, 2016

My Big Belly I

30 x 20 cm

framed size: 53 x 43 cm

Mania Akbari, 2016

My Big Belly II

30 x 20 cm

framed size: 53 x 43 cm

Mania Akbari, 2016

My Big Belly III

30 x 20 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

Mania Akbari, 2016

My Big Belly IV

30 x 20 cm

3 editions plus 2 APs

PRESS RELEASE

Night - An essay on the series by Mania Akbari

By Nick Hackworth

The Night (1553-55) by Michele di Rodolfo del Ghirlandaio and The Allegory of Fortitude (1560-62) by Maso da San Friano are two allegorical Renaissance paintings identified as being amongst the earliest depictions of breast cancer.

“The first case”, report the researchers who are engaged in detecting pictorial representations of different types of pathological conditions, “represents a malignant neoplasia in the central region of the left breast with progressive nipple retraction. In the second case, the feminine figure shows an ulcerated, necrotizing breast cancer and associated lymphoedema.” In layperson’s terms, the left breast of Night appears to have partially collapsed in on itself having, presumably, been eaten away by something, whilst the left breast of the figure of Fortitude in da San Friano’s painting appears enlarged and discolored by subcutaneous stains of gray and black.

For the researchers, aside from forming part of a quixotic exercise in training the diagnostic abilities of medical students, these presumed identifications provide anecdotal contributions to a debate within the scientific community concerning the prevalence of cancer in antiquity, helping refute the idea that it is a quintessentially modern disease. For Mania Akbari, the acclaimed Iranian artist and filmmaker, the two Renaissance paintings in question and the paleopathological study of them, has inspired The Night, a new series of staged, quasi-allegorical photographs that form the main body of work at Akbari’s solo show at Hamzianpour and Kia in Los Angeles.

As with all of Akbari works The Night is a rich interweaving of multiple threads of meaning and reference: personal, political, social, historic, symbolic and aesthetic. It continues the focus of her creative work in recent years on the self, gender identity, body image, trauma and disease, often articulated through the lens of graphically and emotionally intimate, autobiographical content. Perhaps, above all, Akbari’s practice across art and film is the ongoing creation of a reflective and protean space in which the self can bear witness to and shape and express itself in the face of adversity and change. Struggle and trauma has shaped much of Akbari's life and experience. Alongside many Iranian creatives, Akbari is a political exile who was viciously targeted by Iran's punitive theocratic regime. She is a survivor of multiple cancers, of multiple, major invasive and reconstructive surgeries and medical procedures as well as the kinds of more personal and emotional issues common to the human experience.

The ten, dramatically staged images feature Akbari, posing nude, as the central protagonist. Shot in the home that she shares with her partner and artistic collaborator Douglas White and their young son, the images playfully dance on the line between the casual and the formal. The visual elements are resolutely domestic. Akbari is posed in relation to, variously, her son (whose face is not pictured for privacy), strange, found pieces of wood that White uses in his art, flowers, a cup of tea and most significantly, an oversized, plastic dinosaur which features with apparent ambiguity as both a harmless toy and a tongue-in-cheek symbol of omnipresence of threat that exists even in midst of everyday life. The compositions however, are unexpectedly and captivatingly formal, echoing the heighted, dramatic style and symbolic space of allegorical Renaissance paintings. The playful contrast of the domestic context and semi-formal style imbues the series with a gentle and knowing bathos.

Most immediately The Night evolved from a series of playful, performative images that Akbari began making and showing on Instagram in 2022. Most are surreal and absurd self-portraits, highlighted with dramatic makeup. In other set-ups, Akbari, face obscured, wears mustard color stockings that bulge, alien-like, thanks to strategic stuffing with spherical fruit and vegetables, seemingly taking their visual cues from the sculptures of Louise Bourgeois and Sarah Lucas.

Akbari’s two most recent films also provide critical context for The Night. A Moon for My Father (2019) made with White, is a beautiful, subtle, multilayered, epistolary film, structured around the reading out of a series of personal and expansive letters exchanged between Akbari and White. Exemplifying its critical reception, Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian described the film as “digressive-poetic cinema, connecting images and ideas on a dream-associative logic… This is a completely unique and revelatory piece of film-making.” Whilst the film is complex and polyvalent, a consistent, narrative element in the film is the documentation of a series of serious medical procedures that Akbari undergoes. It opens with a graphic scene of Akbari being photographed in hospital after a double mastectomy. In subsequent footage the viewer follows reconstructive surgery, the removal of her ovaries to pre-empt a recurrence of cancer and rounds IVF treatment.

In a voiceover in How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish (2022) Akbari simply and directly states the raison d’etre of the film: “I want to reclaim my body. I am not making a film, I am gazing into your gaze”. With the film Akbari tells a story of the exploitation and subjection of women and their bodies by the male gaze in Iranian cinema. She does so by editing together dozens of archival clips taken from nearly seventy films that span Iran's film history, from the silent era to just after the Islamic Revolution, with shots of herself being tattooed on her chest with the floral pattern we see in The Night. In the clips from films that are all banned in contemporary Iran we see women as imagined and filmed from a male perspective; dancing women, women eager to marry, intoxicated women, women in underwear, women running around in short dresses. Akbari, as in all her art, is a counterpoint of agency and narrative self-determination.

In this revisionist, critical and emancipatory spirit it is worth considering the gender and power relations at play in the depictions of del Ghirlandaio’s The Night and da San Friano’s Allegory of Fortitude. In the Renaissance period women modeling nude for artists was not socially or morally acceptable. Anonymous servants and prostitutes, it is thought, often provided the service. In contrast to Akbari’s agency and self-representation, we will of course, never know the names of the women who modeled for these artworks, nor hear their experiences of enduring disease or trauma. Accordingly it is grimly ironic that, for these paintings, their bodies were not only subjected to the male gaze but also pressed into symbolic service as allegorical personifications. In the case of del Ghirlandaio’s The Night, it may, in fact, have only been part of the model’s body that was used and depicted. The figure is a painterly rendering of Michelangelo’s sculpture Night that, with its companion figure Day, adorns the sarcophagus of Giuliano de’ Medici in Florence. Based on appearances Michelangelo’s modeling of the figure may be an example of his well known tendency to use male models in the studio that he subsequently transformed into female forms in his final paintings and sculptures by ‘grafting’ breasts onto the figures. So the figure’s left breast with its “malignant neoplasia… [and] progressive nipple retraction” may well be visually orphaned from its original body. It is a possibility that conjures a bizarre, oblique connection with Akbari’s double mastectomy and subsequent breast reconstruction. Akbari’s work is an often visceral reminder that historically, globally and in the context of contemporary Iran, her agency to speak and express as a female creative is a rare anomaly.

Akbari's body, in The Night, is, in contrast with its condition in earlier shots from A Moon For My Father, apparently 'whole', the breasts reconstructed and, following the ‘process’ scenes in How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish now decorated with an extensive floral tattoo. This physical fact, combined with Akbari’s seemingly calm, confident and even wryly smiling demeanor in the self portraits, infuses the series with a sense of quiet resilience. Indeed in an inversion of the typical visual semiotics of allegorical images, the familial and domestic elements in The Night suggest that Akbari, the series’ protagonist, has, on a personal level, weathered the violent storms of recent years (documented in her previous works). She is anchored in herself, in her space, with her family. Yet, due to the quasi-allegorical style of the images, there is a heightened sense of a narrative that is still unfolding. Perhaps the resilient domesticity of The Night will be a reprieve only, in a lifestream of changes and challenges. Following the horror movie logic of the possessed child’s toy, perhaps the oversized dinosaur could, indeed, be an insidious harbinger of danger.

There is some irony in Akbari employing an even casually allegorical mode. Allegory derives from the Latin allegoria, meaning “veiled language”. In Akbari’s art and films, of course, little is veiled. Indeed in conventional contemporary art terms, her work would be typically labeled ‘confessional art’ being “art that focuses on an intentional revelation of the private self”, adjacent to the art of, amongst others, Louise Bourgeois, Nan Goldin and Tracey Emin.

The term ‘confessional art’, of course, feels increasingly outdated, carrying with it the tortured moral prejudices of traditional Christian culture. Besides which, in the social media age in which self-exposure of private lives and self-publishing is ubiquitous, what power and meanings are still possible for confessional art? A pressing question for an artist such as Akbari who has been expressing herself in autobiographical mode for the best part of twenty years, significantly predating social media. Has it been rendered obsolete through familiarity or, conversely, does this popularity intensify its possibilities and meanings in the cultural firmament? Quality of artistry and depth of meaning and thought are, principally, what separates a crude social media overshare from confessional art. A standard ‘pay-off’ for audiences of both autobiographical social media content and confessional art is the experiencing of an empathic, quasi-personal connection with the content producer / artist.

Certainly Abkari’s art, in its skillful directness and autobiographical authenticity, allows for just such connections. However there is a still more compelling quality to the work: the intelligence which informs Akbari’s self appointed role of artist-as-witness. It is a quality Bradshaw acutely captures in his Guardian review of A Moon For My Father: “It is a film which calmly, almost miraculously, avoids the tones of tension or trauma or ostentatiously courageous humor that might otherwise characterize a conventional Anglo-American documentary treatment. Instead, Akbari insists on finding a way of thinking about it that transcends her own feelings: she almost always looks in emotional control – a function, perhaps, of her directorial control.”

What the act of making or appreciating her work does for Akbari, only she (perhaps) knows. But what, alongside the poetics and artistic elements, might experiencing the autobiographical element of Akbari’s work do for its viewers? In his Poetics Aristotle describes some of the purpose and effects of drama. Catharsis, the “effecting” of “a purification” of the emotions “through pity and fear” is the best known and most pertinent to our age of promiscuous vicarious identification with remote subjects, be they fictional or real. Anagnorisis, the moment that the hero suddenly recognises their true situation (rarely favorable) and to an extent who they are, is less well known. Clear-eyed, self-knowledge is, perhaps, a rarer quality to savor and understand perhaps, than catharsis. Tonally, Akabari’s work feels like an ongoing articulation of a state of anagnorisis, a foregrounding of that part of ourselves that witnesses and reflects on our life and experience.

The self is not unitary. We are all in lifelong conversations with ourselves. Much art is a reification of these conversations. Beyond indulging the basic human prejudice that consciousness is, in philosophical terms, a good in and of itself, the practice of articulating self-knowledge through art, serves, in its dynamic manifesting of the artist as both subject and object, to transcend the accidents and chance that shape our daily lives. It is a practice made all the more poignant when a significant portion of the experience has been suffering and trauma. Akbari’s art is the willful carving out, through acute thought and feeling, of an autonomous zone of being, an ethereal and esoteric freedom.

Nick Hackworth is a writer and a curator. He is Director of Modern Forms.

www.nickhackworth.com / www.modernforms.org

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia

The Night, 2023

installation view at Hamzianpour and kia